Juan Flores is professor of economic history at the University of Geneva. Mitu Gulati is professor of law at the University of Virginia.

When governments issue bonds they usually have to provide plenty of disclosure to entice investors. These days this often includes information on the country’s environmental, social and governance standards — the now-infamous acronym ESG.

But what about in the mid-19th century, when many countries were autocracies and some were facing civil wars over questions such as whether to abolish slavery? As a logical matter, you’d think that investors would care about such matters.

After all, domestic turmoil over an institution such as slavery — particularly where slave labour was considered crucial to production in important and politically-influential sectors of the economy — should matter to bond yields. Yet there’s barely any mention in the research on slavery and sovereign debt of the views, let alone involvement, of investors in the resolution of such matters. Was this a topic that investors cared about?

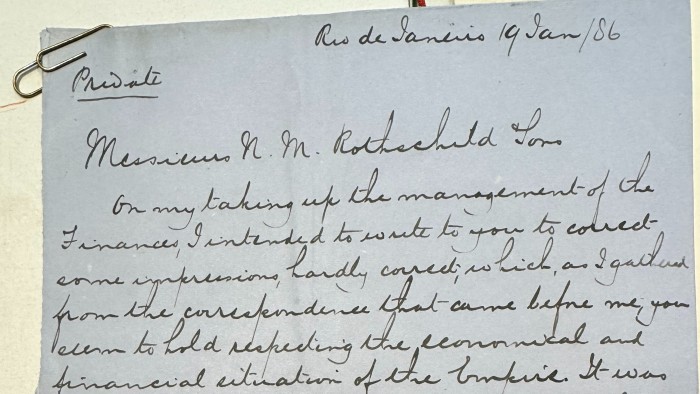

A letter from 1886 that we stumbled upon in the Rothschild Archive in London suggests that at least some did.

In the box for a Brazilian bond issue from February 26, 1886, there was a letter from a Brazilian government official, Mr. Belisario, to the Rothschild Bank in London, responding to the concerns of British investors about the progress being made in Brazil towards abolishing slavery.

The clerks of the bank typically filed letters in boxes labelled “correspondence”. But this one was not. It was, unusually, in the box for the bond contracts. (Archivists tend not to disturb the original filing of material). This indicates that the Rothschild bankers thought it was important and relevant to investors in Brazilian bonds, despite the finances of Brazil being in good shape in 1886.

Here’s the main discussion of slavery in the letter dated January 19, 1886.

To: Messieurs N.M. Rothschild & Sons:

On my taking up the management of the Finances, I intended to write to you to correct some impressions, hardly correct, which, as I gathered from the correspondence that came before me, you seem to hold respecting the economical and financial situation of the Empire.

. . .

[An] apprehension indulged in by those who [study/watch] the affairs of Brazil [is the] the slave question, or the transformation of slave labour into free labour. This subject, which has agitated the public mind here as much during nearly two years, has entered upon a state of calm and peaceful solution, which we must regard as definitive, seeing that the law lately voted contains in itself the means of abolishing slavery completely in the space of 14 years, a period sufficient to let the change be effected without confusion . . . or great injuries. And as the conservative party has just assumed the direction of public affairs, & it may be taken for granted that sufficient time will be reserved to effect the solution to the problem, nothing unforeseen is to be feared in this business, which besides, in some provinces is being considerably advanced without inconvenience.

What was going on? At the time, accurate information about goings on in nations as distant as Brazil was hard to obtain. One function that the Rothschilds performed for clients was to obtain and provide information — and their long standing relationship with Brazil (one that started in the 1820s) meant that they were a trusted source of good information.

Investors clearly wanted to know about what progress was being made towards abolishing slavery, and the correspondence reflects the Rothschilds attempting to obtain this information.

Why did investors care? We cannot tell from the letter, and we couldn’t find anything that spelt out the Rothschild concerns that triggered it. One possibility is that investors were simply worried about how much it would cost to compensate the landed elite, who were pro slavery, to acquiesce to abolition. After all, the £20mn cost of the UK’s own 1833 Slavery Abolition Act amounted to about 40 per cent of the government income that year.

Another could be that investors were worried about possible political strife over the question of abolition. Given that this was 1886, memories of the destruction caused by the 1861-65 US civil war were probably still fresh. The Brazilian Emperor, Don Pedro II, abhorred slavery, but he faced opposition from plantation owners that were the monarchy’s primary support, so domestic turmoil was hardly unthinkable.

Finally, one intriguing possibility is that the Rothschilds’ mainly British clients simply disapproved of slavery, and wanted it abolished to keep buying the country’s bonds.

At the time, there was considerable hostility to slavery in Britain, including from the British government specifically vis-à-vis Brazil. And as the historian Niall Ferguson has shown, the Rothschilds were not above using the promise of bond issuance to cajole countries into adjusting their policies to better appeal to the sensitivities of British investors.

The first example was an 1818 bond issued in London on behalf of Prussia. To secure the issuance’s success, Nathan Mayer Rothschild, then the head of the powerful London branch of the banking family, insisted on a mortgage on royal lands, and influenced a subsequent debt decree that earmarked revenues to service Prussia’s debts and enshrined a ceiling on them that could only be changed “in consultation with and with the guarantee of” the Prussian Estates, the country’s proto-popular assembly.

This arguably represented a subtle imposition of British political standards on Prussia — possibly the first ever example of what we today would call ESG. As Nathan Rothschild wrote to the Prussian finance minister:

[To] induce British Capitalists to invest their money in a loan to a foreign government upon reasonable terms, it will be of the first importance that the plan of such a loan should as much as possible be assimilated to the established system of borrowing for the public service in England, and above all things that some security, beyond the mere good faith of the government . . . should be held out to the lenders.

. . . Without some security of this description any attempt to raise a considerable sum in England for a foreign Power would be hopeless[;] the late investments by British subjects in the French Funds have proceeded upon the general belief that in consequence of the representative system now established in that Country, the sanction of the Chamber to the national debt incurred by the Government affords a guarantee to the Public Creditor which could not be found in a Contract with any Sovereign uncontrolled in the exercise of the executive powers.

By 1886, Nathan Mayer Rothschild had passed away, but his family had helped establish London as the dominant financial centre and themselves as the world’s most influential financiers. Anyone who needed to borrow large sums of money would have to do it in London, and probably through the Rothschilds.

Whatever the core cause of the concerns, the Brazilian letter writer clearly saw it as important to assure the House of Rothschild that the move towards abolishing slavery was progressing in an orderly and peaceful fashion. Moreover, this wasn’t the only echo of modern disclosure standards. The letter also stresses that Emperor Don Pedro II was in good health and expected to continue in office for many years — an assurance of political stability for investors.

So how did things turn out? Just two years after the date of the letter, as opposed to the 14 years contemplated in the letter, Brazil abolished slavery. But the promise of political stability proved less reliable. In 1889 there was a coup d’état that swept aside the Brazilian monarchy, and Pedro II died in Parisian exile in 1891. Oops.

Nonetheless, while an old regime’s foreign advisers usually get shown the door when governments falls, the Rothschild-Brazil relationship survived. In fact, when Brazil hit financial turbulence in the 1890s and was at risk of failing to repay their prior bonds, the Rothschilds helped Brazil raise new money to stay current with investors.

What is today’s relevance of this? Well it shows that investors and investment intermediaries have long cared about how borrowers tackled the major social issues of the time, and could use money to subtly influence behaviour.

The negative reaction that bond investors had to president Donald Trump’s threats to fire the chair of the Fed — and Trump’s subsequent U-turn — are an example of this today. (We’re willing to wager that there are communications between the heads of big financial institutions today and the Trump administration saying “we are worried about your periodic threats to fire Jerome Powell”). For bond investors, the Rothschild letter represents the 1886 version of ESG.

But most of all, we think it’s just a fun story, perfect for the long weekend.