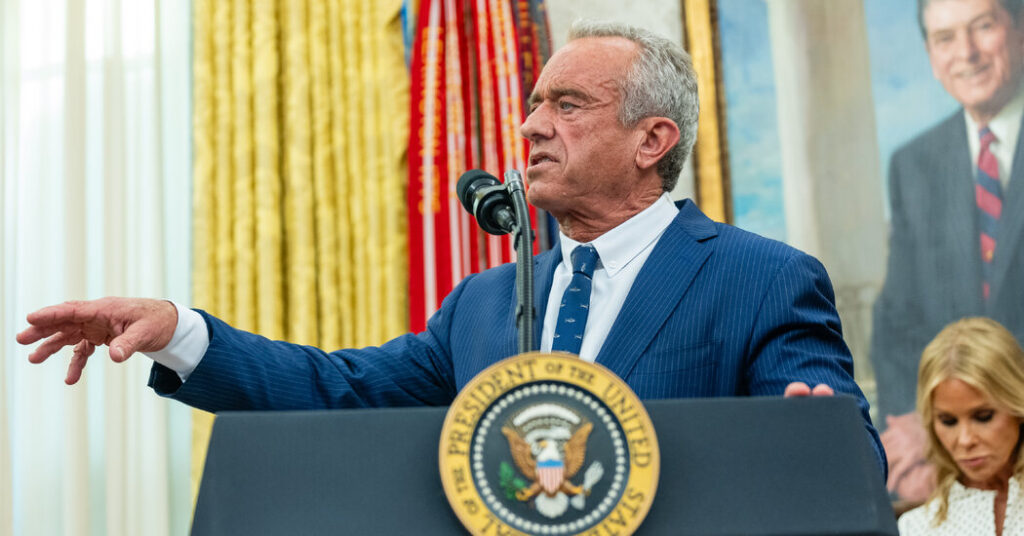

Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. made a show on Facebook of his meeting with American Indian and Alaska Native leaders last month, declaring himself “very inspired” and committed to improving the Indian Health Service, which he says has “always been treated as the redheaded stepchild” by his agency.

Now Native leaders have some questions for him.

Why, they would like to know, did he lay off employees in programs aimed at supporting Native people, like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Healthy Tribes initiative? Why has he shuttered five regional offices of the Department of Health and Human Services that, by the estimate of one advocate for tribes, cover 80 percent of the nation’s Indian population?

Why were five senior advisers for tribal issues within the department’s Administration for Children and Families, all of them Indian or Native people, let go? Why are all of these changes being made without consulting tribal leaders, despite centuries-old treaty obligations, as well as presidential executive orders, requiring it?

But the final indignity, Native leaders say, came last week, when Mr. Kennedy reassigned high-ranking health officials — including a bioethicist married to Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, a tobacco regulator, a human resources manager and others — to Indian Health Service locations in the American West, when what the chronically understaffed service really needs are doctors and nurses who are familiar with the unique needs of Native people.

“They are breaching their trust obligation to Indian tribes by all of the scams that they’re doing,” said Deb Haaland, the former interior secretary and congresswoman, who is a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe and a Democratic candidate for governor of New Mexico. “It’s terrible, it’s shameful and it isn’t right.”

This week, Mr. Kennedy will visit Native health providers and meet with tribal leaders in Arizona and New Mexico to spotlight his commitment to Indian health. The secretary, who has also been invited to appear before the Senate health committee on Thursday to testify about the job cuts and the vast reorganization of his department, has spoken often of his and his family’s longstanding commitment to Native Americans. The Coalition of Large Tribes, an advocacy group, gave his nomination its highest endorsement.

“I spent 20 percent of my career working on Native issues,” Mr. Kennedy told Senator Lisa Murkowski, Republican of Alaska, during his confirmation hearings in January, adding that his father and his uncle, former Senator Edward M. Kennedy, “were deeply, deeply critical of the functioning of the Indian Health Service back in 1968 and 1980, and nothing’s changed.”

He vowed that if confirmed, he would bring in a Native person as an assistant secretary “to make sure that all of the decisions that we make in our agency are conscious of their impacts on First Nations.” The department has a Secretary’s Tribal Advisory Committee, which met with Mr. Kennedy last month.

The Indian Health Service, a network of hospitals, clinics and health centers, some operated by tribes themselves, flows from a series of treaties and court rulings that obligate the federal government to provide health care to American Indian and Native people — an obligation that can be traced back to 1787, when the Constitution recognized “Indian tribes” as sovereign nations. The people it serves have profound health challenges.

Native Americans have long had shorter life expectancy and higher rates of disease than other ethnic groups. According to an analysis published last year by the National Council of Urban Indian Health, white people born in 2021 are expected to live an average of 11 years longer than their American Indian and Alaska Native peers. Native Americans die disproportionately from chronic liver disease, diabetes, homicide, and suicide, according to the Indian Health Service.

A spokesman for Mr. Kennedy noted that the service itself had not been affected by the recent layoffs, and said there were no plans to consolidate any of its offices. (One tribal leader, Aaron Payment of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, said that was not true; Indian Health Service workers in his area were told to cancel their lease on a local office, he said, and didn’t know where they would go.)

The spokesman said the proposed transfers were voluntary, although legal experts said those who refused would be subject to termination without severance pay. The spokesman would not say how many employees were affected.

But in interviews, more than half a dozen leaders of Native American groups used words like “cruel,” “disingenuous” and “offensive” to describe the proposed transfers. Cruel because the administration gave workers one day to decide whether to uproot their families in order to keep their jobs; disingenuous because the moves seemed aimed at getting rid of high-performing employees who might otherwise be difficult to lay off; and offensive because they play into the racist trope that the regions served by the program constitute a backwater.

Some chose their words carefully, fearing that if they angered Mr. Kennedy or President Trump, it would make things worse for the people they represent. A.C. Locklear, who runs the National Indian Health Board, a nonprofit representing the nation’s 574 tribes, was asked whether he viewed the recent job transfers as a serious effort to improve the health of Native Americans.

Mr. Locklear, an attorney and citizen of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, was silent for a long while. “I’m not exactly sure how to answer that,” he finally said.

Legal experts say the transfers are permissible under the law. Those affected hold positions within the senior executive service, a corps of high-ranking government employees created by Congress in 1979 to give agency heads more flexibility in transferring people with executive skills.

Two employees who got transfer notices said they had been placed on administrative leave and cut off from their work email accounts. One said she would consider a reassignment, despite the hardship for her family. Another said she had turned the offer down. Both spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution. Dr. Fauci’s wife, Christine Grady, declined to be interviewed.

David Simmons, the government affairs and advocacy director for the National Indian Child Welfare Association, a nonprofit in Portland, Ore., said it looked to him as though the administration was waging pressure campaigns to push senior leaders who are not familiar with Indian tribes into jobs for which they are not suited.

“That’s a huge waste of time, and it’s an ineffective and inefficient way to get business done,” he said.

He also said his group had worked for years with the health department to put together a team of five advisers for Native issues within the Administration for Children and Families, a sub-agency of the health department. He learned that all five had been laid off as part of last week’s “reduction in force” that eliminated 10,000 employees.

“It’s an incredible loss,” Mr. Simmons said.

Tribal leaders have long labored to be treated as equals by American politicians. But, they say, never have they struggled as much as under Mr. Trump.

Even before Mr. Kennedy was confirmed by the Senate, Mr. Trump’s assault on diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives infuriated Native Americans, who felt forced to explain that programs that serve them should not be eliminated. “We’re not racial minorities; we are political minorities,” Mr. Simmons said.

Mr. Trump’s hiring freeze and mass firing of probationary employees prompted a string of letters from the National Indian Health Board, demanding that the Indian Health Service be exempt from the cuts. According to Abigail Echo-Hawk, an epidemiologist and citizen of the Pawnee Nation who is a leader of the Seattle Indian Health Board, tribal leaders “were able to educate Secretary Kennedy,” and 950 employees were reinstated.

But while Native leaders expected such moves from Mr. Trump, many say they feel betrayed by Mr. Kennedy. As an independent presidential candidate, he visited with the Coalition of Large Tribes and spoke of his family trips to the Rosebud Sioux Indian Reservation, the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and Hopi and Navajo reservations while he was a child, according to Last Real Indians, a news organization that covered the event.

“This was very much a part of my youth,” he was quoted as saying, adding that his father, who was killed in 1968 while running for president, “believed the treatment of Indigenous people in this country — the Native Americans, the ones who above all others can call themselves American — that that was the original sin of our country.”

Mr. Payment, who served on the Secretary’s Tribal Advisory Committee under three presidents, including during the first Trump administration, said in an interview that he believes Mr. Kennedy is genuine. He blamed Elon Musk, who is leading an effort to overhaul the government,. He wrote on LinkedIn that while Mr. Kennedy “cleans up good for his new role and had a collegial interaction” with the committee, “major cuts are happening right under our noses with his consent.”

Ms. Echo-Hawk, who made headlines in 2020 when she criticized the C.D.C. for not sharing data about Covid-19’s spread among Native communities, said she was especially concerned about the C.D.C.’s Healthy Tribes Program, which seeks to “respect and promote Indigenous knowledge, traditions, and cultural practices for health and healing.”

The program provides grant funding that supports Ms. Echo-Hawk’s work. She said she learned through agency contacts that the head of Healthy Tribes and many of its employees were let go, and that the C.D.C. Office of Tribal Affairs would most likely be broken up, its components transferred to other divisions.

As “a friend of Indian Country,” she said, Mr. Kennedy “has eloquently stated that one of his first focuses is going to be on chronic disease prevention for American Indians and Alaska Natives — which is why this move is so puzzling.”

Ms. Haaland, who said she used the Indian Health Service for her health care as a younger woman, used another word to describe the reorganization, layoffs and transfers: disrespectful.

“It’s disrespectful of the I.H.S., it’s disrespectful of the people who have dedicated their careers to H.H.S. and to our country, fighting disease and regulating the things that need to be regulated,” Ms. Haaland said. “I just don’t understand what they think they’re doing.”