The director Claus Guth, wearing a scarf and coat, was pacing the frigid auditorium of the Metropolitan Opera during a recent rehearsal of Strauss’s “Salome,” going over lighting and visual cues. It was only a few days before opening night, and he was optimistic.

“New York can carry you on an enormous, beautiful energy,” he said. “It’s an adrenaline — not a stressful feeling, but a sensation of being alive.”

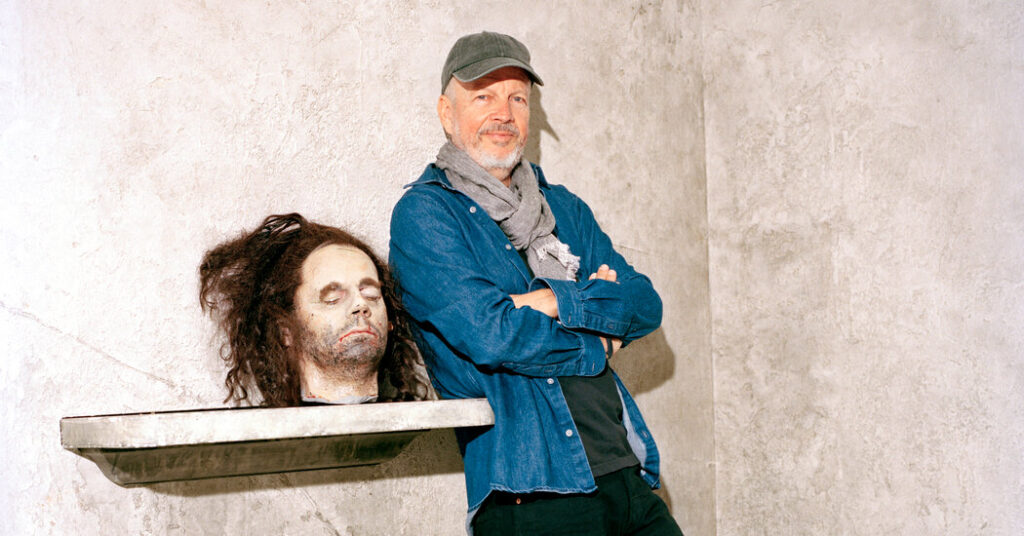

Guth, 61, who was born in Germany and has spent most of his career in Europe, has won acclaim for his experimental, exacting approach to operas new and old. Now, he is bringing those sensibilities to his Met debut, directing a new production of “Salome” that opens on Tuesday.

Inspired partly by Stanley Kubrick’s film “Eyes Wide Shut,” Guth has infused the opera, an adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s decadent retelling of the biblical story, with elements of a psychological thriller. Menacing figures walk around in ram masks on a black-and-white stage. A naked woman appears and disappears. A girl strokes a doll’s hair before pulling out its arms and hitting it violently against the ground.

Guth said he wanted to highlight the suffocating rules of the Victorian society portrayed in Wilde’s play. He focuses on telling the back story of Salome, the 16-year-old princess and stepdaughter of King Herod, portraying her as a victim of abuse and trauma who becomes obsessed with John the Baptist, eventually demanding his head.

“I wanted to bring to life this rigid system — the invisible lines around what is allowed and what is not allowed,” Guth said. “It’s a portrait of a young woman growing up in this world, with its strange rules, trapped in a family prison.”

“Salome” is one of opera’s most emotionally charged and demanding works. For Guth’s staging, the Met has lined up the soprano Elza van den Heever in the title role; the baritone Peter Mattei as John the Baptist (known in the opera as Jochanaan); and the tenor Gerhard Siegel as King Herod. The Met’s music director, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conducts.

Guth’s Met debut is coming somewhat late in his career, but it is the start of a longer-term relationship with the company. In future seasons, the Met will import his 2023 staging of Handel’s opera-oratorio “Semele,” a co-production with the Bavarian State Opera, and his production of Janacek’s “Jenufa,” which premiered at the Royal Ballet and Opera in London in 2021.

Peter Gelb, the Met’s general manager, described Guth as one of Europe’s most inventive directors, saying his “commitment to coherent storytelling” set him apart.

“There aren’t that many directors who are brilliant enough to be original but are also able to tell the story in a way that doesn’t require a guidebook to understand what you’re seeing,” Gelb said.

Guth was born in Frankfurt and grew up in what he has described as “quiet, wealthy surroundings.” As a child, he dabbled in Super 8 films, but he felt he was not being exposed to the gritty realities of life. He moved to Munich for college, studying philosophy, literature and theater, with dreams of becoming a film director.

In his 20s, he had an epiphany about opera while working as a camera assistant on a production at Bayreuth, the festival in Germany that Wagner founded nearly 150 years ago. In this art form, Guth saw a way to combine his interests in music, theater and visual art.

“Suddenly, it clicked,” he said. “My passions came together.”

He rose swiftly in the European theater scene, with celebrated stagings of contemporary operas like Luciano Berio’s “Cronaca del Luogo” at the Salzburg Festival in 1999. He garnered praise for his unconventional approach to classics, especially those by Strauss and Wagner, including the “Ring,” “Der Fliegende Holländer” and “Tannhäuser.”

When Gelb approached Guth about staging a new “Salome,” he already had a production under his belt at the Deutsche Oper in Berlin. But Guth wanted to create something entirely different for his Met debut.

“It’s boring for me to do the same thing,” he said. “I need risk.”

The Met’s “Salome” was originally planned as a co-production with the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow, where it premiered in 2021. After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, though, the Met cut ties with the Bolshoi and built its own sets for its staging.

For his “Salome,” Guth said, he wanted to give the title character a sense of agency — to show that she’s “not just the puppet and product of her education.”

“It’s the biography of Salome — the development of a young person,” he said. “I was looking for something that everybody could connect to.”

Nézet-Séguin said that Guth had made “Salome” freshly relevant by shining a light on the abuse of children and vulnerable people. “He manages to emphasize a story that is really telling for our times,” Nézet-Séguin said, “without detracting at all from the opera.”

The Dance of the Seven Veils, one of the opera’s defining scenes, is often portrayed as a striptease. But in Guth’s version, the dance is a moment of reckoning, as seven versions of Salome, including van den Heever, portray the horrors of her upbringing.

Van den Heever said Guth had created a “dance of the fragmented mind, of the subconscious.”

As a “six-foot-tall person who is supposed to be in the body of a 16-year-old,” van den Heever said, she initially found it difficult to inhabit the character. But, she said, she was helped by Guth’s clear vision of the opera and an emphasis on working as an ensemble.

“You are always part of a greater story,” she said. “You’re part of a tableau, of a painting.”

In the lobby of the Met recently, Guth basked in the morning sun before heading to rehearsal. Although he has not worked at the Met, he is no stranger to New York. In 2023, he brought a show called “Doppelganger” to the Park Avenue Armory, staging Schubert’s “Schwanengesang” as a dreamscape in a soldiers’ hospital.

He first encountered the Met in the 1980s, when he came to New York for an internship at CBS. Back then, as a young man, he bristled at the traditional, gaudy look of some productions. But he found himself drawn to the music. Decades later, he appreciates the energy and focus of the Met’s singers, orchestra players, staff and crew.

“The Met is enormous, but it sometimes feels very intimate,” he said. “I feel immense joy and gratitude. I feel at home.”