Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Chinese politics & policy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

China has pledged to open its markets to more products from Pacific Island nations, increase economic assistance and step up support for their fight against climate change as the US retreats from the largely impoverished but strategically contested region.

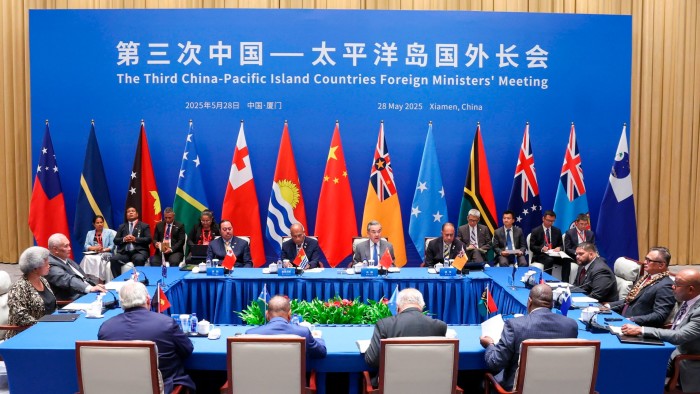

Hosting foreign ministers from 11 Pacific Island countries in Xiamen, Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi promised $2mn to combat climate change in the region and offered to accelerate negotiations for bilateral trade deals under which the region could export more to China.

Since President Donald Trump took office in January, the US has drastically cut its foreign aid assistance to poorer countries, increased tariffs globally and retreated from climate negotiations — a move seen as offering an opportunity to China.

“China stressed that there is no political strings attached to China’s assistance, no imposing one’s will on to others, and no empty promises,” according to a joint statement of the Third China-Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers’ Meeting.

The meeting on Wednesday and Thursday was Wang’s first round of talks with Pacific Island nations since Beijing’s attempt to agree a comprehensive security deal with them failed in May 2022 over fears of creeping military influence.

The proposed deal also triggered a pushback from countries that have traditionally held more influence in the region, including Australia, New Zealand, Japan and the US.

But officials and analysts said Beijing was now trying to take advantage of the fallout from Trump’s policies.

“They’ll be making the most of it. China is now seen as a more reliable partner over the US,” said Blake Johnson, analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s Pacific Centre.

Matt Thistlethwaite, Australia’s assistant minister for foreign affairs, said: “Obviously, the Trump administration’s economic policies have created some uncertainty.”

China has been increasing its official development aid to the region from a multiyear low in 2022 and has replaced a significant portion of the loans that used to dominate those flows with aid grants.

Thistlethwaite this month travelled to Fiji, Tonga and Vanuatu with foreign minister Penny Wong to discuss climate action, security and issues including illegal fishing and drug trafficking with Pacific leaders and offer what they said was a “clear signal of commitment” to the region.

Anna Powles, associate professor in the Centre for Defence and Security Studies, Massey University, said the US position on climate had also enabled Beijing to move closer.

This week’s statement made no mention of security.

But a list of deliverables from the meeting released by the Chinese foreign ministry included a goal to hold a fresh round of talks on police and law enforcement co-operation this year and mentioned an “Initiative on Strengthening Practical Maritime Cooperation”.

Mihai Sora, director of the Pacific Islands programme at the Lowy Institute think-tank, said China could push to increase the presence of its coastguard in the region, to regularise ship visits to Pacific Island countries and step up military exchanges.

“Their strategic objective of building acceptance for an increased Chinese military presence in the region has not changed — they are just attempting to recast it in terms that will be less controversial,” he said.

While analysts said the ministerial meeting’s outcomes were more symbolic than substantial, the line-up showed that Beijing was making gradual inroads.

The number of participating ministers increased from eight in 2022, a reflection of Nauru’s move to switch diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China last year and the Cook Islands’ move closer to Beijing.

Johnson said this showed China’s more patient approach was bearing fruit. Beijing had “learned the lesson” from its failed attempt to get a broad security deal three years ago and “will now take the long path”.