“I really believe that we all do contain multitudes,” Andrew Scott said on a Friday morning in March. Scott may contain more than most. An actor of unusual sensitivity and verve, he is starring, solo, in an Off Broadway production of Chekhov’s melancholy comedy “Uncle Vanya.” The title, like the cast list, has also been condensed, to just “Vanya.”

The New York transfer of this London production had opened a few nights before. In this version, the playwright Simon Stephens has relocated the action from 19th-century Russia to rural Ireland in more or less the present day. Scott plays the central character, a man who has sacrificed his own ambition to support his feckless brother-in-law. He also plays the brother-in-law, the put-upon niece, the neglected young wife, and several others. Scott is alone onstage throughout. That stage can feel very crowded.

The New York Times critic Jesse Green described Scott, in performance, as a “human Swiss Army knife.” Mindful of Scott’s work in “Fleabag,” “Ripley” and the recent film “All of Us Strangers,” Green also referred to Scott as a “sadness machine.” This is a popular opinion. Variety has called him “Hollywood’s new prince of heartache.”

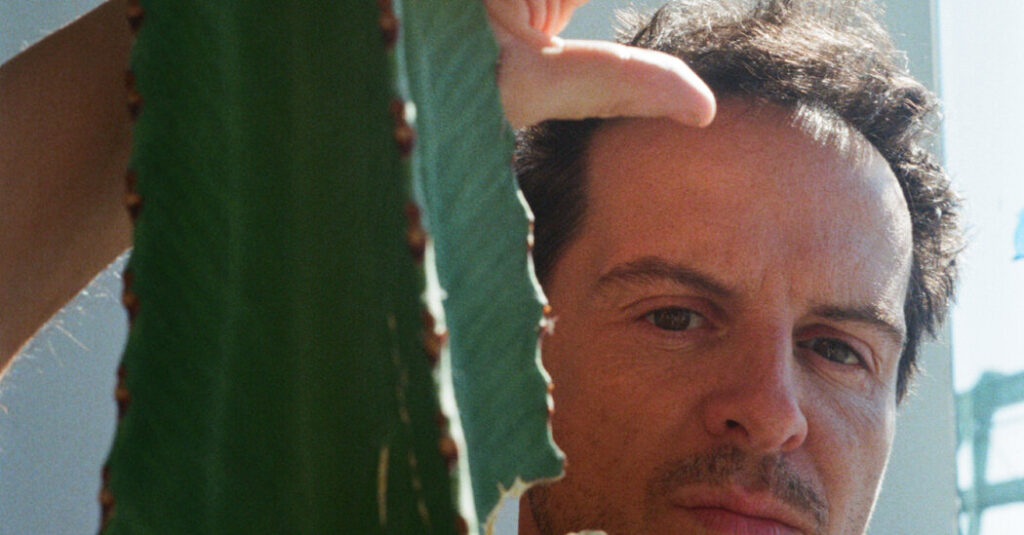

On this morning, Scott, 48, did not appear unusually sad, though he was somewhat rumpled. The plan had been to walk over to Little Island and then along the Hudson River, toward the theater, but severe weather had changed that.

“Oh my God, it’s windy,” he said, out on the street. (“You can’t get sick,” his publicist fretted.) So Scott had retreated, with a breakfast burrito and a Day-Glo orange juice, to the shelter of a nearby pier. Its windows looked out onto the river. The water — choppy, gray-green — reflected in his eyes.

In person, Scott is serious, though he wears that seriousness lightly. And if his intelligence and empathy are obvious, he wears these lightly, too. Vanity eludes him. (Even aware he would be photographed, he arrives with his hair looking like it has never known a comb.) And I thought, as he sat cross-legged on a bench, wearing a nubby brown cardigan, that I have rarely met an actor with less pretense or affectation. Later he took off that cardigan. On his red shirt, a heart was embroidered, just over the breast.

Scott did not plan to play all the roles in “Vanya.” Despite moving the action to Ireland, Stephens, a playwright with whom Scott has often collaborated, had written a more traditional adaptation of the play. But during an early read through with Stephens and the director, Sam Yates, Scott had a scene in which he took both parts. Something electric happened.

Initially, despite that electricity, Scott resisted. He worried that playing all the roles would feel like a gimmick or perhaps an empty exercise. But as he got to know the play better, he began to see the connections among the characters. “They’re all just talking about their own very particular pain and how it’s a very singular thing,” he said. “Actually, all of them are much more similar to each other than they say.” Having a single actor onstage, erasing the physical difference between the characters, would only emphasize this.

Rehearsals were rigorous, but also magical in their way. Learning the lines was hard — “so [expletive] hard,” Scott said, but then again he had played Hamlet, so he could handle it. He didn’t want to do elaborate accents, though close listeners, and Irish listeners in particular, will distinguish differences of class and locale among the characters. And costume changes (Scott wears his own clothes throughout) were nixed. So he contented himself with finding gestures and small props to define each person. Michael, a country doctor, bounces a tennis ball; Ivan, the Vanya of the title, wears sunglasses and toys with a sound-effects machine; Sonia, Ivan’s niece, wrings a dishrag. As the play goes on, these props and gestures fall away and it’s only Scott’s energy that defines the roles.

“You don’t want the audience going: Which one is this?” he said. “But you do want them to do a little bit of work, a little bit of leaning forward.”

Somehow it all succeeds. Even in scenes in which Scott has to canoodle with himself, there is clarity. And surprising heat. (If you are one of the legions of fans obsessed with Scott’s Hot Priest character on the TV comedy “Fleabag,” maybe it’s not so surprising.) “It’s representing sex in a very fundamental way,” he said. In every scene, Scott is incredibly specific in where he looks, how he stands, where he places the other characters. Sometimes, alone onstage, he has to adjust his step so that he won’t run into them.

“It’s just an endless experiment,” he said. “I’m still learning about it all the time.”

Scott doesn’t think he’s any more sad than most people, though he knows that he often plays sad characters, the “Vanya” ones among them. (He also, worryingly, has a line (“Ripley,” “Sherlock”) in psychopaths.) He recognizes his talent for empathy and he knows that he is perhaps better at understanding and conveying emotion than most. “But not just sadness,” he said. “I laugh very easily. The idea that people are sensitive or vulnerable in some ways, I find very, very beautiful. So I don’t have fear of that. Or at least I don’t have a big fear.”

And really, what’s more universal than sadness?

“Who isn’t sad?” he said. “Like, who isn’t sad? I don’t get that.”

“Vanya,” on its face, is a play about wasted potential. So it’s the gentlest kind of irony that in performing it, Scott isn’t wasting his. Sometimes that prospect is daunting. “It’s a potentially scary thing to think that you might live up to your potential every time you do the play,” he said. Often he wakes up in the morning and thinks he won’t be able to do it again that night. But then he does, making himself a vessel for humanity, in all its multitudes and contradictions. As an actor, he’s just large enough to contain it all.

“The fact that we all behave in absolutely monstrous, beautiful, completely contradictory ways as human beings, that’s what my job is to represent,” he said.